When I dabble with paint, my mind’s eye envisages an accurate reproduction of the Mona Lisa. When I pick up my guitar, I imagine myself being able to caress it the way that Leo Kottke can (if you have never heard of Leo Kottke, get yourself one of his CDs, and relish in his authority over the instrument). And when I try to sing, that little voice inside my head (not the one that comes out of my mouth) sounds just like Van Morrison during his classic performance of Caravan in The Last Waltz.

Now I must confess that I don’t paint much, because my Mona Lisas end up looking like stick women (and poor ones at that), nor do I pick up my guitar as often as I used to (because after years of practice, all I have been able to master is a very approximate rendition of CCR’s Proud Mary). And I have finally acquiesced to the protestations of those people around me who beg me to stop singing because it sounds more like finger nails on a blackboard then Van the Man.

Yup, it has taken me over 40 years to appreciate that I have about as much creative skill as a door knob. On the other hand, I often reflect that my biology has given me the capacity to at least aspire to great heights of artistry.

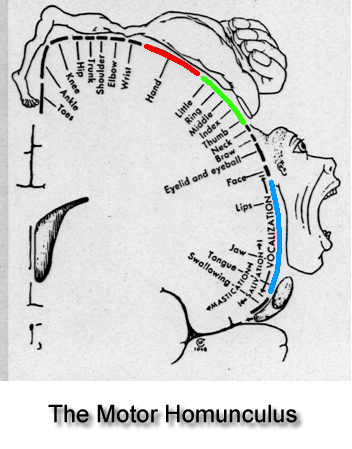

In my last entry, I tried to make the point that our sensory cortex partly defines our humanity. That lesson is impressed more forcefully when one considers the motor cortex. Recall that the sensory cortex is the area of the brain that responds to sensory input from different areas of your body. The motor cortex is responsible for getting different parts of your body to move or act. As with the sensory cortex, Wilder Penfield was responsible for mapping the motor cortex (or homunculus), and this map is illustrated below:

When I look at this representation, there are two features that attract my attention. The first is the amount of motor cortex that is devoted to the hands and fingers (highlighted in red and green, respectively). This biological prioritization provides us with our manual dexterity. It is what allows us to pick a guitar, to tinkle the ivory keys of a piano, to use a paint brush to capture the exquisite mystery of La Gioconda’s smile, to thread a needle, to type on a keyboard. It is also for this reason that we are able to exploit the tools we have invented as skillfully as we do. Our closest cousins, chimps and the great apes, are definitely capable of inventing and using tools for different purposes (using a twig to entice ants from their holes, for example), but they certainly can not use tools with the precision that we can. All the training in the world will not allow a chimp to use a chisel as expertly as an accomplished woodworker. Nor will it allow the most nimble-fingered ape to approximate Duane Allman’s guitar work on Layla.

The other expanse of motor cortex that garners my admiration is that devoted to control of the mouth, tongue and vocal cords (highlighted in blue). It takes a lot of computing power to be able to entice your vocal cords, your tongue and your lips into just the right configuration to hit that perfect note, and that computing power is abundant in the motor cortex. The extent to which the motor cortex is devoted to controlling the mouth and throat also explains why we communicate verbally. Did you know that the initial attempts to train chimps to learn language involved trying to teach them to actually speak (i.e. vocalize words)? Chimps also have a motor cortex, but the area of cortex devoted to vocal control is restricted relative to what you see in the human animal. Their brains are just not built for the detailed vocalizations you need to in order to pronounce all the phonemes that comprise linguistic verbal communication. Neurologists knew this, and had the chimp trainers consulted a neurologist before starting, they would have saved themselves years of wasted effort, and moved directly to the more realistic goal of seeing whether chimps could learn sign language (although chimps may not have the manual dexterity that we do, they can control their fingers and hands with sufficient agility to sign).

Now, don’t get me wrong. I am not saying that tool use or language are uniquely human skills. Primates (and other animals) use tools; there is no debate about this. And although the scientific jury is still out on this question, there is accumulating evidence that chimps and apes have more developed communication skills then we originally thought. So it’s not a black and white dichotomy, but rather a relative distinction. My point is that humans have a more developed potential for tool and language use, and this potential arises in large part because our brains are assembled a little differently then those of our primate relatives. Not better, just different. So when I strum my guitar and it doesn’t sound anything like Leo Kottke, I don’t wallow in self-remorse, I thank my lucky stars that my brain has given me the capacity to at least aspire to that lofty goal.

Tagged as Brain, communication skills, language, motor cortex, senses, sensory cortex.

Posted on 23 Jul 2009

On Jul 24th 2009 at 09:10

Joe, I enjoyed your blog. I do have a neophyte’s question concerning the cerebral cortex – the role it plays in organizing the mind and its limitations at this stage of our evolution.

Can the cerebral cortex reconfigure a brain’s design, i.e. put the eco back in economics?*

Our gift of forethought put us to the top of the food chain but I am under the impression (please correct me if I’m wrong) that the cerebral cortex is not equal to the next necessary step in our evolution.

In Herman Hesse’s book, The Glass Bead Game, he anticipates a collective fixation with virtual reality. I believe economics has become our virtual bead game, We’re progressively more and more out of touch with the reality of Nature that generates us.

My intuition is that the next step in our evolution will come at a significant human price. What is a cerebral cortex to do?

Chard

* Forethought may have thrust us to the top of the food chain but lately we seem more likely to devolve for a while before we find our new footing…

On Jul 24th 2009 at 09:26

Hey, Chard:

Thanks for the kind words. More importantly, your “neophyte questions” have inspired the topic for my next entry. “Evolution” has to be considered within the context of the mechanisms that drive it. Darwin recognised that evolution can be driven both biologically and culturally. This is the key to your question, and I con’t have the space here to develop the response with the sophistication it requires. So stay tuned…